ARTICLE AD BOX

Donald Trump campaigned on a promise to rapidly and brutally expel millions of immigrants.

In his first 100 days in office, he has bent every part of the government toward that goal, cracking down on non-citizen activists, invoking emergency wartime authorities, skirting court orders to stop deportation flights, pulling humanitarian protections from hundreds of thousands, and attempting to ignore the Constitution and end birthright citizenship.

In a White House defined by chaos, immigration may be the only place where the Trump administration is consistent.

For the millions of immigrants across the U.S., this has meant consistent anxiety. Will they be detained and deported without warning? Do they still have rights to protest? Will the courts check Trump, and will Trump obey the courts?

Four different immigrants and their families told The Independent about what it’s like living through this age of uncertainty.

An asylum seeker from El Salvador mysteriously arrested in Louisiana

The first sign that something was wrong came when Wendy Brito, an asylum-seeker from El Salvador, attended one of her regular check-ins with immigration officials in Louisiana last month. She called her fiancé, Kremly Marrero, and said she heard the sound of handcuffs nearby.

“I said, ‘Don’t worry, you’re not doing anything wrong. You got permission to stay here,’” Marrero told The Independent. “‘You applied for asylum. You should be alright, don’t worry about it.’”

Brito hasn’t been home since. She was arrested and sent to an Immigration and Customs detention center in the city of Basile, Louisiana, nearly 200 miles away from where the couple live with their three children, just outside of New Orleans.

“My kids are not sleeping. My kids are constantly depressed,” Marrero, a U.S. citizen from Puerto Rico, said. “They break down at school crying…They’re constantly asking why their mother is in jail if she’s not a bad person.”

And he’s not sure what to tell them. He said he still doesn't know why Brito, who first applied for asylum in 2009, was suddenly arrested after nearly two decades. Marrero said he suspects it may have had something to do with a long-ago incident in which a neighbor called the police on Marrero and Brito during a domestic dispute in which neither sought charges.

Brito fled El Salvador after a gang killed her brother in the midst of an extortion attempt on the family, and her life has been turned upside-down once again.

The immigration officer who arrested Brito said it had something to do with the new administration, Marrero’s lawyer told him, but that’s about all he knows.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement acknowledged a request for comment about the case from The Independent but did not respond to questions.

“She went in for a routine check-in with ICE and never made it home,” Congressman Troy Carter, Democrat of Louisiana, said on April 22, after a delegation of representatives visited Brito and others held at facilities in Louisiana’s “deportation alley.” “That’s a tragedy. Due process was clearly denied…This is America. This is not some third-world country.”

In between four-hour nights of sleep, caring for the kids, and working in facilities at a local hospital, Marrero speaks with Brito on a prison video tablet. He said his partner has become unwell behind bars.

“I’m looking at her. I know you’re not eating,” he said. “She says, ‘I don’t want to. I just want to go home.’ That breaks you. I don’t care how strong of a man you are. You see your wife there and you can't do anything. I feel hopeless.”

While Brito has been in detention, a new crisis has hit the family. Marrero just found out he has liver cancer. He’s still working to understand the severity of the diagnosis, but so far he has ignored his doctors’ pleas to stay in the hospital, he told The Independent.

“I didn’t have anyone to take care of the kids, so I had to leave. We’re waiting for her to come home so I can get treated,” he said. “It’s been very tough.”

There has been one bright spot though. Marrero said Brito’s bond has been approved, and the father is hoping to raise some of the $5,000 payment on GoFundMe so Brito can return home ahead of a May asylum hearing.

An Ohio grad student in the legal ‘gray zone’ for his activism

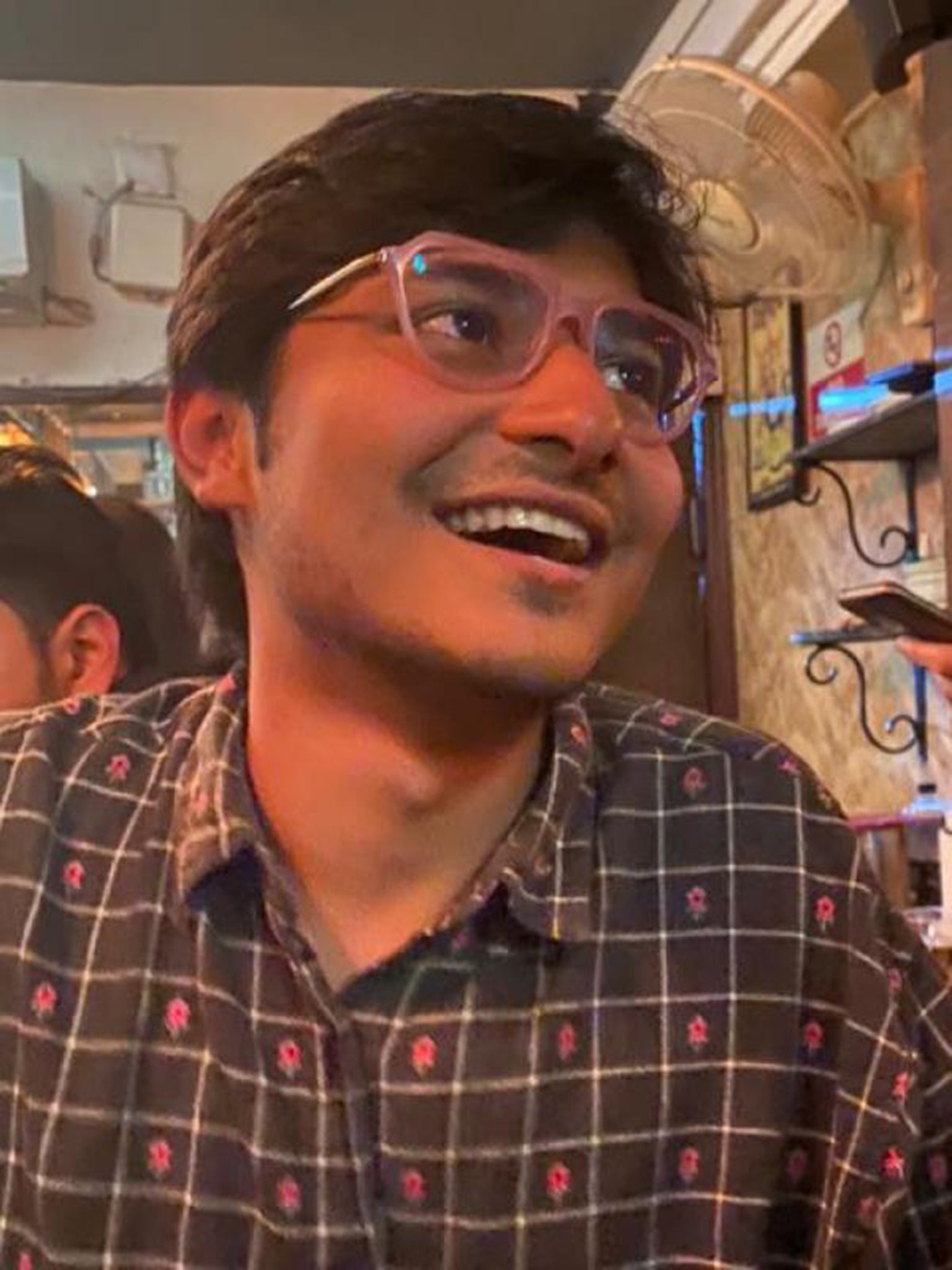

Ahwar Sultan, 25, a graduate student at Ohio State University, was sitting in an architecture lecture on April 3 when he got a notice that his record within the SEVIS government exchange student database had been terminated, jeopardizing his ability to study and work inside the U.S.

The government said vaguely that Sultan may have lost his visa or that his name may have appeared in a criminal records check, while the university said it hadn’t gotten any notice from the government about the change.

The timing was hard to miss, though. The Trump administration had vowed to deport all non-citizen students who joined in widespread campus pro-Palestine demonstrations. It also said it would investigate universities for alleged antisemitism, including Ohio State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio confirmed in late March the State Department had begun pulling hundreds of visas.

Sultan had been a part of campus Palestine activism since 2023. The 25-year-old, who studies right-wing politics in India, felt compelled to join the movement out of a mixture of his academic background and a sense of solidarity with Palestinian scholars, who watched as Israel destroyed or damaged every university in Gaza.

Sultan may have come on the radar of authorities for an April 2024 incident where he was arrested as he attempted to protect a group of Muslim protesters at a divestment protest conducting evening prayers from advancing police. The resulting charges were later dismissed and expunged.

Still, the notice from the feds put him in a legal “gray zone,” he said. He temporarily stopped attending class in person or conducting his duties as a teaching assistant. If he loses his ability to work for the university, he’s not sure he’ll be able to cover his bills, let alone stay in America.

“I don’t feel safe being out and about, especially getting the news from everywhere around the country,” he told The Independent after his status was pulled.

On April 15, Sultan and a campus Palestine group sued the Trump administration, arguing its efforts to surveil and deport immigrants over their alleged views violated the First Amendment, and, in Sultan’s case, due process and federal law as well.

Federal officials argued in court documents that Sultan’s lawsuit was wrongly conflating canceling his status in the database with revoking his immigration status overall or beginning to deport him from the country, decisions he could contest in immigration court while being afforded full due process.

On April 24, Washington federal judge Tanya Chutkan ordered Sultan’s status in the SEVIS database be temporarily reinstated, arguing the administration could “point to no legal authority” for canceling it in the first place, while voicing doubt over the administration’s larger treatment of the student.

“At this juncture, more than two weeks have elapsed since Sultan filed his Complaint and the court is highly skeptical of counsel’s representations that Defendants are still waiting for ICE to confirm whether Sultan’s presence in the United States is unlawful,” she wrote.

Despite the temporary win, Sultan isn’t feeling very reassured. He got a letter from the U.S. Consul General General in Mumbai, informing him his F-1 visa had been revoked, meaning he may not be able to re-enter the country if he leaves it.

The grad student, who decided to pursue his studies in America to avoid the potential of government interference, now feels the U.S. is following Israel down what he sees as a path of lawlessness. Even if he gets some measure of reprieve in court, he feels the paradigm has shifted, noting that even his friends and colleagues without visa issues fear leaving the country.

“A pure sense of normalcy is not going to return. All bets are off,” he said. “There might be ways to mitigate the uncertainty and try to push back against it. I don’t really see how, with an administration that is turbocharging ICE and attacks on immigrants, any real sense of safety will return for most people.”

Ohio State declined to comment, citing the ongoing lawsuit.

A Haitian translator who can’t return home, but may not be able to stay in America

Billy Elve, 32, is also waiting on the courts.

The Orlando, Florida, resident is originally from Haiti, and arrived in the U.S. in February 2024, granted temporary protected status and humanitarian parole under a Biden administration initiative.

He fled Haiti as gangs increasingly took control of the country and threatened his neighborhood.

“They forced their way into his house, tied up the husband, and went away with his wife,” Elve told The Independent of one neighbor. “At that time my wife was pregnant, so we had to move.”

Elve managed to get approval to come to the U.S., but his wife Nehemie and daughter Villyncia’s attempts were still pending as Trump took office.

The translator has felt a variety of emotions since — worry for his family, alarm at the Trump campaign’s racist conspiracies about Haitians eating cats, and uncertainty after the administration sought to end the CHNV parole program in March, which covers some 500,000 people from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela.

A federal judge blocked the move in mid-April, prompting the Trump administration to appeal, and Elve doesn’t know what will happen next. If he returns to Haiti he’ll be marked as a target, an expat returning home from the wealthier United States, while if he stays in the U.S., there’s still no guarantee his family can escape.

“It’s very difficult to know what can be done next,” he said. “There's a big question mark behind that.”

On Monday, he learned from immigration officials his wife and daughter definitely won’t be able to get in on the same parole program as he did, which Homeland Security has taken to calling “an unlawful scheme” from the previous administration.

Now he’s considering joining his parents in Canada and seeking asylum, or pursuing a change of status in the U.S. to be a student or on a company-sponsored visa, whatever gets his family out of harm’s way fastest.

“It was already a pain and now it’s just adding oil to the fire,” he told The Independent.

An activist who fled the country

Momodou Taal, a UK-Gambian grad student at Cornell and campus pro-Palestine leader, felt he couldn’t wait on the U.S. courts for protection.

Taal sued the Trump administration last month with a group of fellow academics, alleging a pair of January executive orders had effectively made it illegal for non-citizens to protest the administration and its allies like Israel.

As the constitutional lawsuit proceeded, immigration officials told Taal to surrender immediately and officers circled near his residence.

Court documents later revealed that ICE was notified on March 14, a day before the suit was filed, that the State Department pulled Taal’s visa, with officials claiming his protest actions had created a hostile environment for Jewish students. The threat raised the prospect he might be deported before a court could rule on his challenge.

Taal grew up in a political milieu, where family members served in The Gambia’s post-colonial government, and told The Independent he saw his own Palestine activism as a way to continue their legacy of fighting colonialism. He said he has never supported antisemitism of any kind, pointing to a letter of support from Jewish Cornellians, and only advocates the right to resist what he sees as an illegal occupation of Palestine under international law.

Still, despite his faith in his convictions, he felt his leverage in the U.S. slipping away as he hid out in a friend’s apartment in Ithaca, barely eating and avoiding communicating with family for fear of being tracked.

“Given that I dared to challenge Trump and challenge his executive orders, I felt they would make an example of me,” Taal told The Independent from an undisclosed location, as he prepares to return to the UK.

The Trump administration has defended its handling of the Taal case.

“It is a privilege to be granted a visa to live and study in the United States of America,” the Department of Homeland Security said after he fled the country. “When you advocate for violence and terrorism, that privilege should be revoked.”

It wasn’t an idle fear that something exceptional might happen in or outside of court. The same day as Taal filed his suit, the government invoked the wartime Alien Enemies Act to summarily deport alleged gang members, many of whom say they have no ties to criminal groups, and wrongly deported a man to El Salvador, despite a court order specifically barring his removal to the country.

And Taal had watched for months as Trump spoke more and more specifically about the mass deportation of non-citizen Palestine activists.

“I felt like it was only a matter of time until something happens to me, unless I triumphed in court,” he said. “I didn't think it would be so quick.”

Now, as Taal works to finish his degree remotely, he said he gets messages from other activists asking when he knew it was time to leave America.

Every person has a different threshold, but it’s clear that for the millions of immigrants in the United States something fundamental about the country has already changed.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·