ARTICLE AD BOX

Giant icebergs the size of Norwich were drifting off the coast of Britain during the last ice age, according to a new study that has uncovered their existence.

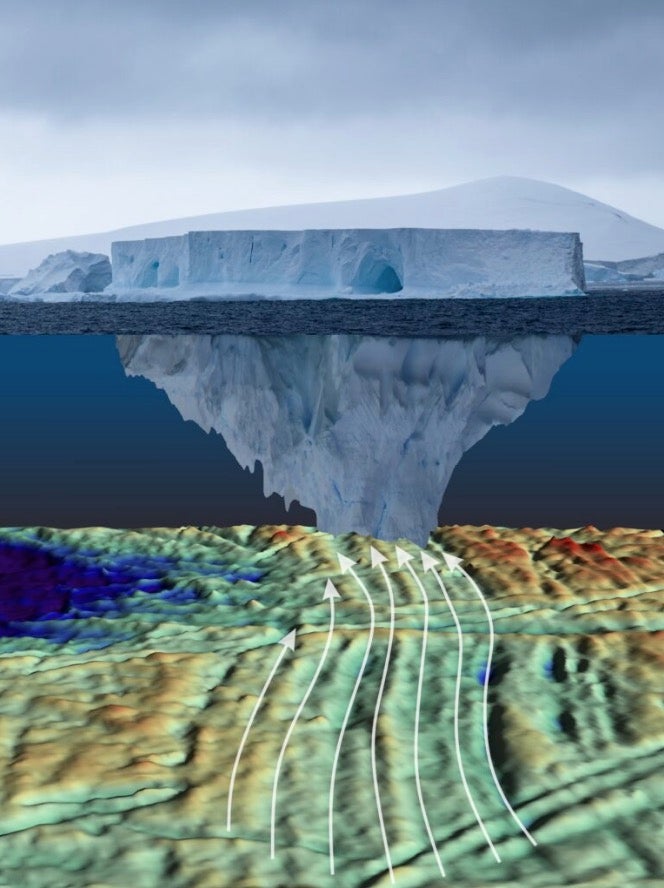

The underbelly of massive "tabular" icebergs that dragged across the North Sea seabed between 18,000 and 20,000 years ago left behind a sequence of characteristic, comb-like grooves that were discovered preserved in sediment close to Aberdeen, Scotland, the researchers said.

During this time, an ice sheet covering much of the British and Irish Isles was retreating due to a warming climate.

The new research, published in the journal Nature Communications, could indicate how current climate change and global warming are impacting Antarctica.

Scientists from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) discovered the evidence in seismic survey data used to locate drilling platforms in the Witch Ground basin, which lies between Scotland and Norway.

Researchers could then estimate the dimensions of the icebergs responsible from the size of the parallel grooves.

“We’re talking about enormous flat-topped, or ‘tabular’, icebergs,” BAS marine geophysicist Dr James Kirkham, the lead author of the study, said.

“Conservatively, they measured five to perhaps a few tens of kilometres in width — comparable to the area of a medium-sized UK city such as Cambridge or Norwich — and could be a couple of hundred metres thick.”

The wide Witch Ground tramlines are the first definitive evidence that enormous blocks of ice were also moving across the North Sea, although single grooves created by the small bergs' narrow keels have been seen previously, the scientists said.

In Antarctica, tabular bergs are discharged from ice shelves – the floating fronts of glaciers that have flowed off the land into the ocean. Around 75 per cent of the continent is surrounded by these buoyant platforms.

The integrity of the ice sheets depends on these structures, which buttress and retain glacial ice that would otherwise flow into the ocean.

The regular breakaway of tabular bergs at the leading edge of shelves helps to maintain the glaciers to their equilibrium.

Co-author Dr Kelly Hogan said: “We can actually document the catastrophic collapse of these ice shelves at the end of the last ice age using our data, because around 18,000 years ago we detect a shift in the type of iceberg plough-mark recorded in seafloor sediments, from giant tabular bergs – produced by the normal calving lifecycle of ice shelves – to much more numerous and smaller icebergs as the ice shelves disintegrated.”

In Antarctica, there are currently very few instances of this transition behaviour. What happened to the Larsen B ice shelf, however, may be the best example.

Over just one week in 2002, warming created several ponds of meltwater near the platform's surface, which seeped down through the ice and broke it up into numerous little bergs.

The glaciers that were previously held back behind the ice shelf accelerated by several times their original speed following its collapse, which enhanced their contribution to sea level rise.

This phenomenon appeared to happen in the North Sea between 18,000 and 20,000 years ago when the British and Irish ice sheet was shrinking rapidly by 200-300 metres a year at its edges.

“It’s an interesting question that goes to the heart of how ice shelves influence the modern Antarctic Ice Sheet. If we observe a similar transition from large tabular icebergs to smaller icebergs, it could indicate the continent is about to experience significant and rapid mass loss,” BAS co-author Dr Rob Larter said.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·